As hospital doctors working in acute care, we have a considerable amount of control over the scene in which we work. Our ED resus bays have adequate space, lighting, and equipment (which is in the same place every time we need it). We have a huge number of team members we can draw upon for support in our patient care, and with prehospital notification of impending patient arrival we can assemble an appropriate team, set up relevant equipment ahead of time, and establish control over the scene before the patient arrives. We even have waiting areas for family and friends of critically ill patients and can delegate staff to look after them while a resuscitation is occurring.

In the prehospital setting, many of the factors above are unachievable, and to doctors this represents both a source of challenge and considerable discomfort.

One of the most interesting aspects of working as a doctor in the prehospital setting (both in practice and simulation) has been watching my paramedic colleagues in action at a prehospital scene – in particular the skill, calm, and aplomb with which they assess and manage a prehospital scene, and the adaptability with which this process occurs under highly variable circumstances.

While as HEMS doctors it would be uncommon for us to be in a position where we have a significant role in scene management – this role would usually be performed by ambulance staff already at the scene or by the helicopter paramedic – it is important for us to understand the process.

There is comparatively little literature available in this area. There are resources detailing ASSESSMENT of a scene, such as this chapter from the Prehospital Trauma Life Support manual.

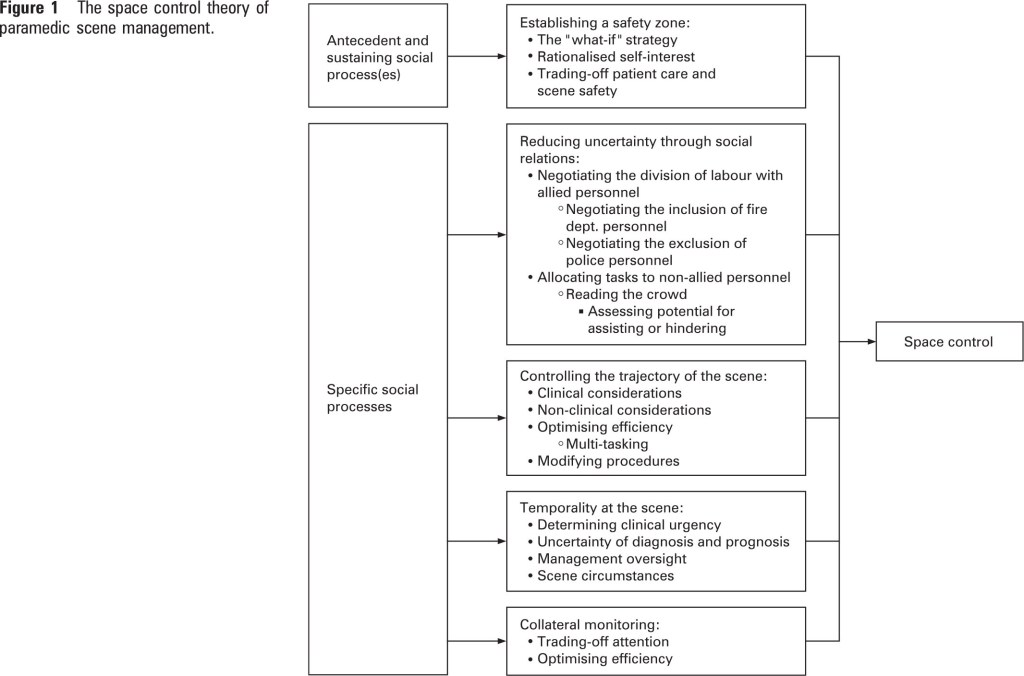

With regards to MANAGEMENT of a prehospital scene, the authors of this study, published in EMJ in 2009, conducted interviews with experienced paramedics to generate a theory as to how paramedics manage a scene. The model that resulted was called “the space control theory of paramedic scene management”, which states that paramedics manage a scene by controlling the activities that occur in the space immediately around the patient “Space” is interpreted to include both physical and human (non-physical) elements.

“Although there are physical realities that present problems for scene management, for the most part the management of the scene involves how paramedics interact with other people. Indeed, it is through working with others that paramedics are able to solve the problems presented by both physical and human elements. This means that scene management is a dynamic social activity comprised of social processes.”

This figure from the paper provides overview of the theory:

This model has multiple “human factors” elements – analogous to the increasingly recognised importance of human factors in hospital care.

Another useful resource for doctors at a prehospital scene is this 2007 slide set from Tony Smith – ADHB Intensivist, Medical Advisor to St John Ambulance, and Auckland HEMS doctor:

Full-text pdf for this post is available here (secure area limited to ADHB staff only – ADHB has online subscription access to this journal through the Philson Library at the University of Auckland School of Medicine)